With a week or so off in there due to both my wife and I having COVID, things have been progressing. I got one of the torque tubes measured and cut for the wing. The plywood bits for the nose of the aileron ribs all got drilled out. Looking at how to do the aileron build brought up some issues, though. The plans say to glue and clamp those in place — the challenge is in how to do that, exactly. The clamping anyway.

In order to make the job a bit less complicated, I glued up the plywood sandwiches for the two ends and the middle, where the locking pins will install. I spread some epoxy and threaded the pieces onto the cutoff piece of torque tube to get them all perfectly aligned – and they were tight. With everything aligned perfectly, I shot a few 1/2″ 23 ga. micro pins to keep everything stable, then added spring clamps and took them off the tube so they wouldn’t end up glued to it.

Next day I ran those and the 1/8″ ply pieces on a spindle sander with a 3/4″ drum on it to enlarge the holes a bit. I wanted a slip fit on the tube for the thicker pieces, and a more “roomy” fit for the 1/8″ pieces. Those were supposed to get 1-1/8″ holes in the first place, but I missed that part in the instructions and we drilled them to 1″.

Realizing that the wing now can’t sit flat on the steel rail due to the trailing edge of the wingtip bow not being tapered to match the wing, I took care of that as well. Only the last couple inches of the bow need to be tapered. I started with a little razor plane that Dad used for model airplane work to shave the bow lamination and corner block down very close to the contour I wanted. I then finished it up with a sanding block, and I’m quite happy with the result.

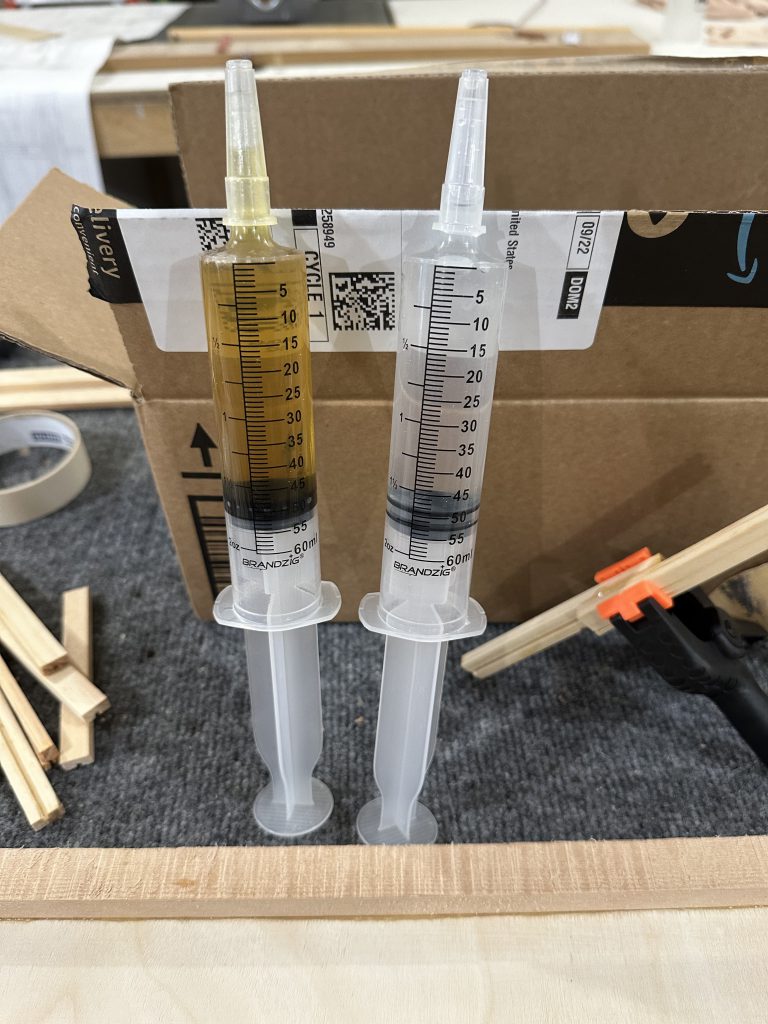

Everything is ready now to get the plywood pieces glued into place. I’d have done it today, but as I was about to mix up the glue I was reminded that it was time to go pick up the grandkids, which turned into dinner and a late arrival home.